Works作品紹介

福島県会津地方十一景 (2012-2014)

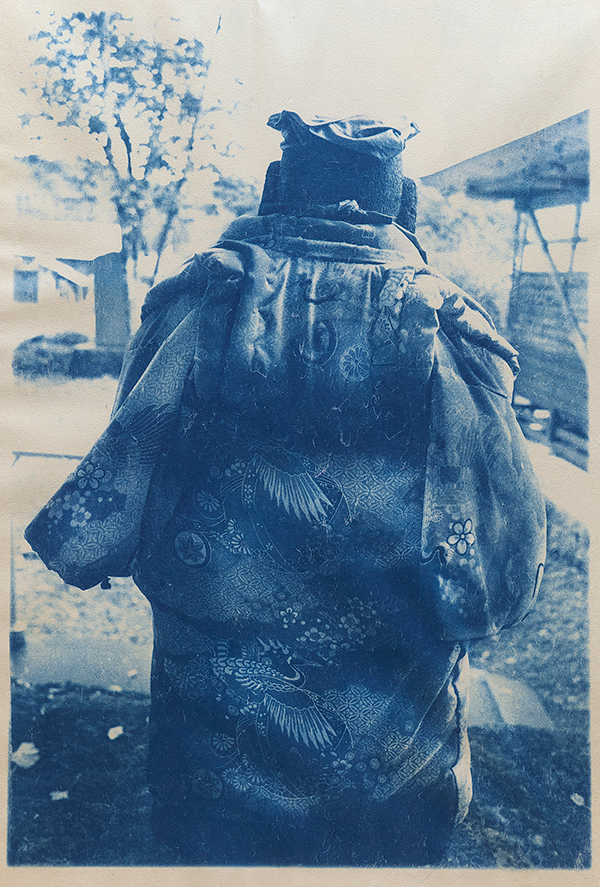

《冬木沢、十王堂》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2012年

《Visiting to Huyukizawa, Juoudou》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2012

福島県会津地方十一景

東北で起きた大きな震災と原発事故のあと、私は縁あって福島県会津地方に通うようになりました。20年前から、岩手の山間で過疎の集落となった「父の家」に通い撮影してきた私は、奥会津の山裾に広がる田畑や信仰の跡、雪深い風景に出会ったとき、岩手の風景と重なって見えてきて、この場所に親近感を覚えました。

お世話になったおじいさんやおばあさんたちは、長い冬の間、みんなでよく集まってお茶を飲み、楽しいおしゃべりをしながら手仕事に興じていました。山から湧き出る冷たく綺麗な地下水は、家々の台所にひかれています。山菜類やキノコ類、栗の実、栃の実、育てた野菜などの食べ物を加工し貯蔵して、毎日料理に使います。また、暮らしの道具を作る竹、山ブドウ、アケビのツルなど、豊富な材料が天井から吊るしてありました。

滞在中、一番印象的だった言葉は、「手を動かせば、宝になる」と、「山に行けば何でもある」でした。手間暇を惜しまず丁寧な仕事をする楽しみ、喜び、地域に残る古い信仰の話などを教えていただきました。

*

人口1,300人の福島県大沼郡昭和村では、600年前から「カラムシ」という背の高い植物を栽培し、苧(お)引き、糸紡ぎ、織りが行われています。

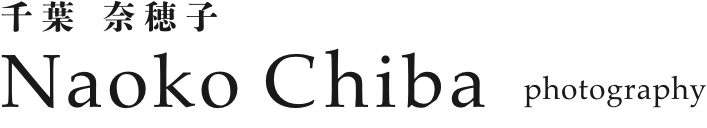

玄関先でカラムシの「苧引き」作業を続けているお母さん。手を休めることなく熱心に続けながら、脇で作業をしているお父さんと私の会話に、ときどき混じってくれます。お父さんは家の奥に行き、ご自身で撮った昔の村の写真や家族の写真を持ってきて、並べて見せてくれました。

その中の一枚は、30年前、お母さんがこの玄関先で、今と同じ姿勢で同じようにカラムシの苧引き作業をしている写真でした。私はちょうど、30年前、お父さんがカメラ越しにお母さんを見つめた位置に座っていました。写真の中には、今は村を離れた子どもたちがお母さんの周りに写っていました。私はお父さんの視点を借りて撮りました。

夏の夕暮れ時。うす暗い玄関で、カラムシの茎は白く光る繊細な糸の束に生まれ変わっていきます。秋まで乾燥させ、冬に紡がれ織られて、来年には、氷をまとうに涼しいとされるカラムシの衣類になるのでしょう。

*

人口1,700人の福島県大沼郡三島町も豪雪地帯です。山ブドウの樹皮やマタタビ、ヒロロを使い、縄文時代の遺跡からも発見される「編み組み」を用いて暮らしの道具を作っています。

私たちは、マタギをしている男性の作業小屋を訪れました。霧が少し晴れるのを待って、みんなで一緒に、志津倉山に登りました。山に入るとすぐに、これがヒロロ、これがミヤマカンスゲ、こっちが山ブドウの木、皮はこう取る、と次々に教えてくれました。熊の巣穴を狙う猟をするときの話を聞いたり、熊が登り降りした爪痕の残る木の下で休んだり、天然のナメコを取ったり、ブナ林の中に突然現れる雨乞岩に驚いたりして下りてきました。

小屋に戻ると、男性は、熊撃ちの話をするときと違う優しい顔で、硬い山ブドウの皮を裂いて籠を編み始めました。誰に編み方を教えてもらったのかを尋ねてみると、じいさんが作ったのを見て自分で覚えた、とおっしゃいました。

11 Views from Aizu, Fukushima

For twenty years, I photographed a dying village secluded deep in the mountains of Iwate in Tohoku for my series My Father’s House.

In the aftermath of the natural and nuclear disasters as a result of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, opportunity brought me time and again to the Oku-Aizu region of Fukushima, another remote part of Tohoku. I sense certain similarities between my home in Iwate and places in Oku-Aizu—with its snowy landscapes, sprawling foothill farmlands, and monuments to bygone beliefs. They resemble the places I saw growing up in Iwate.

The elderly men and women of Aizu spend their winters getting together to work with their hands while chatting over cups of hot tea.

The cold, clear groundwater that flows from the mountains is drawn into the kitchens of every home. The people here live off the land. They regularly gather, process, and store edible wild plants, mushrooms, and a variety of nuts, which they incorporate into their everyday cooking. Indigenous plants such as bamboo, wild grapes, and vines like the akebia quinata are used to make everyday tools that can be found hung from the ceilings of homes all over the area.

“The most precious things are born when you put your hands to work.”

“The mountains have everything you need to survive.”

The ideas of the Aizu people left a strong impression on me during my stay. I learned the joys of doing something right without cutting any corners as well as the old spiritual beliefs and folklore that remain in the area.

*

Mishima-machi, a remote town of 1,700 in western Fukushima Prefecture, is in an area of heavy snowfall.

The people here make household items by hand, using the skins of wild grapevines, catnip, and hiroro, an indigenous sedge grass, and weaving them together with a technique called amikumi. Traces of amikumi can be found as far back as the Jomon period.

It was autumn when we visited a local matagi hunter, waiting in his work shed for the fog to clear before making our ascent up Mt. Shizukura. As we climbed the mountain, our guide showed us local plants like the indigenous hiroro and miyamakansuge grasses. He foraged various plants and showed us how to peel the skins off the stems of wild grapes.

The hunter told us he was looking for a bear’s den as we rested under a tree with claw marks. On our way back down the mountain, we foraged wild nameko mushrooms and were delighted at large amagoi boulders that would suddenly appear amid the beech forest. He told us that these boulders were used in traditional rainmaking ceremonies.

Once we returned to the hunter’s shed, he began to tear the hard vine skins into strips and wove them into a basket. His face appeared gentler, a stark contrast from the rough hunter who talked of killing bears. When I asked the man where he learned to weave, he replied that when he was young he would watch his grandfather.

*

The inhabitants of Showa-mura, a village of 1,300 in western Fukushima, have cultivated a tall plant called karamushi, a type of ramie, for over 600 years to produce plant fibers for spinning and weaving.

My photo depicts an older woman seated near the entrance of her home, extracting the fibers from inside a karamushi stalk by hand, a process called obiki.

She worked the whole time I was there, without ever stopping to rest, though she would occasionally chime in while her husband and I were talking.

Her husband disappeared into the back of their home and returned with a stack of old photos he had taken of his family and the town, lining them up in rows in front of me.

In one photo, his wife sat in the same place near the entrance, in the same posture, separating usable fibers from the plant stalk in the same way as she was now. But the photo was 30 years old. I was now sitting where he had sat on that day, so long ago, watching her work through his camera’s lens. Several children, now departed from the village, surround her in the photo. I try to position myself the way her husband had and raise my camera to recreate the same scene 30 years later.

The woman, seated in the dim corridor, transforms the green karamushi stalks into bouquets of delicate thread, which glitter in the waning summer twilight. The threads are dried until autumn and will be spun and woven in the winter. Next year, they will become karamushi clothing, lightweight and cool to the touch.

Translation by Queen & Co.

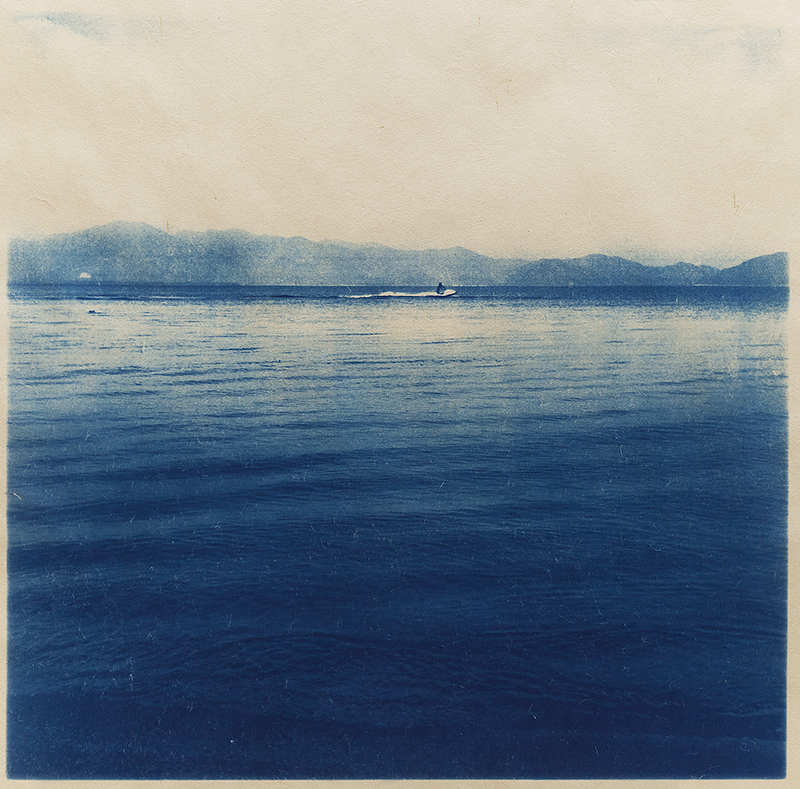

《水上バイク》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2012年

《A water bike》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2012

《水上バイク》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2012年

《A water bike》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2012

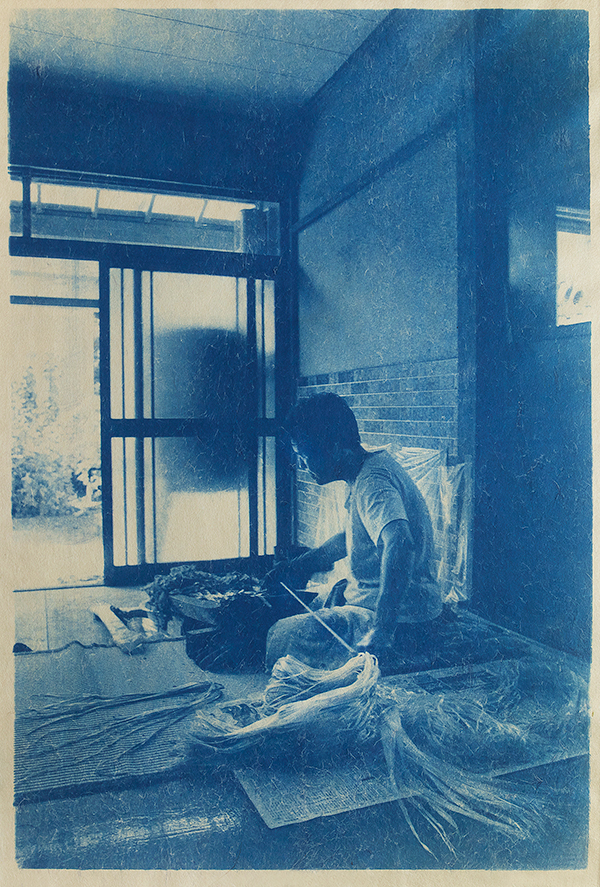

《身不知柿》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2012年

《A mishirazu persimmon》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2012

《身不知柿》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2012年

《A mishirazu persimmon》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2012

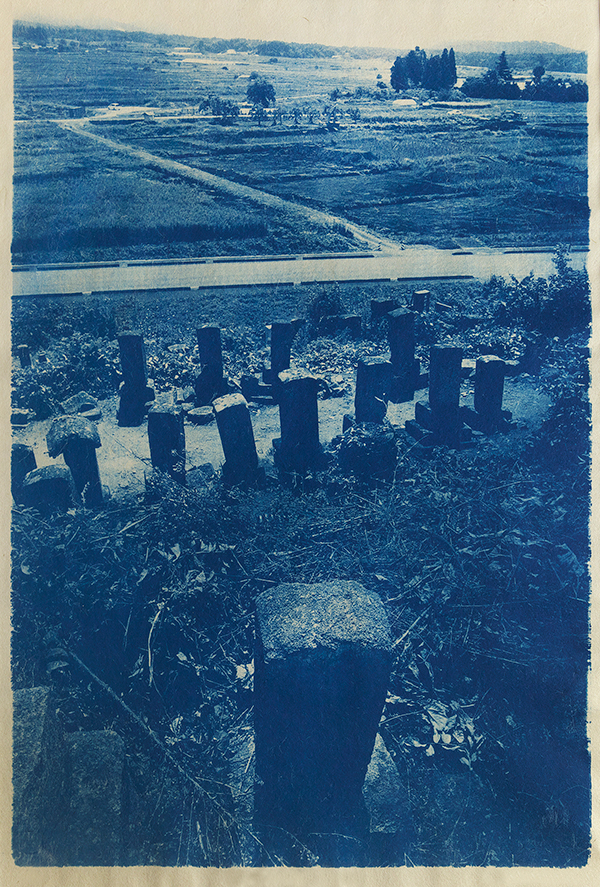

《常世・丘の墓地》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2014年

《Tokoyo, Cemeteries on the hill》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2014

《常世・丘の墓地》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2014年

《Tokoyo, Cemeteries on the hill》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2014

《子安観音さま》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2015年

《Kayasu Kannon》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2015

《子安観音さま》和紙にサイアノタイププリント、2015年

《Kayasu Kannon》Cyanotype print on Japanese paper, 2015